The first steps of design: Mingei VS industrial design

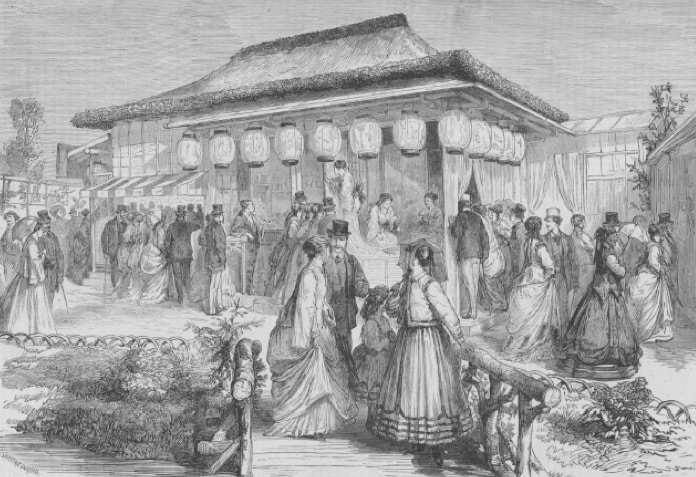

Many changes came from these (new) first moments of exchange: the confidential trend of arranging interiors with Western furniture only reserved for notables spread to a few progressives in the 1920s; the press helped to relay this new trend more widely.

Westernization rhymes with industrialization: while Japanese creation was until then governed by the kogei, literally “traditional arts and crafts”, not distinguishing between the hand and the machine, a growing process of industrialization was going to start on the territory. The creation of the Industrial Arts Research Institute, IARI, in 1928 in Sendai by the Ministry of Trade and Industry is the most eloquent example. In reaction to this recent orientation, the Mingei movement was created under the leadership of the philosopher and art critic Soetsu Yanagi (1889-1961), supported by the potters Shoji Hamada (1894-1978) and Kanjiro Kawai (1890-1966): exalting everyday objects and the beauty of human-made forms, Mingei is centered on craftsmanship and still has strong resonances in contemporary creation, proving the longevity and importance of the movement.

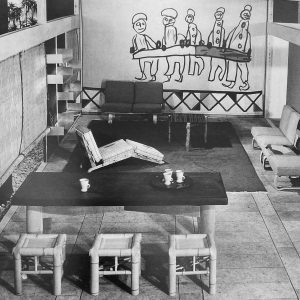

To guide the country’s new industrial branch, IARI, through its supervisory ministry, hosted several important figures from the European Modern Movement. Thus, the German architect Bruno Taut (1880-1938), fleeing the rising Nazism in his country, settled in 1933 and spread his progressive ideas, including the Bauhaus ones – the critic Masaru Katsumi also played a major role in this part; following him, Charlotte Perriand (1903-1999) was invited in 1940, to spread the Modernity she was creating alongside Pierre Jeanneret (1896-1967) and Le Corbusier (1887-1965). The conferences, visits and exhibitions done during the several visits of the designer marked a whole generation of creators; the reciprocal is true because she brought back in her suitcases the Japanese aesthetics, both in forms and ideas.

People and ideas of Functionalism and Modernity traveled in both directions. While the first half of the twentieth century was marked by the arrival of European architects and designers in Japan, the opposite was emerging: more and more Japanese designers went to Europe and the United States to observe industrial processes and distribution methods in situ. After the Second World War, the industrial model became dominant in the archipelago and Japan reigned supreme in one of these fields: technology.

Standing out: Japan and technology

The success of cheap mass-produced items by Japanese industry is relative. While Japan was taking the industrial train, the country was turning to flourishing companies, established since the 19th century, still participating today to the fame of the country: the high-tech, electronics and automobile industries gradually grew and prospered, from Seiko clocks to Toyota cars.

The transposition of the technologies used during the war into the everyday field settled. The first great success in the domestic market was the Toshiba rice cooker (1955), which revolutionized the daily life of Japanese households.

One of the most advanced fields in which Japan excelled was transports area: from its high-speed trains, whose shape was inspired by the American streamline of the 1920s and 1930s, to their cars, this industry, which had long been established in the country, applied new advances, particularly following the Korean War. The first great success was the Honda Super Cub produced from 1958, whose popularity is comparable to the mythical Italian Vespa designed in the same period. The field does not escape the Westernization but it was necessary to wait until 1972 for a Japanese car to fiercely penetrate the Western market: the Honda Civic was a best-seller.

The 1950s and 1960s focused on surface appearance following the advent of the consumer society: going against this global trend, Japan focused on their strengths without evicting the rule because if Japanese objects carry in their DNA the mark of a sharp manufacture and a good design, the form is always harmonious. Pushing the research on high technologies to a whole new level, miniaturization became one of the major assets of the Japanese industry, from Sony electronic devices to Pentel stationery. This can be linked to the small size and finiteness of the Japanese territory, resulting in small spaces and a certain lack of resources: purity, flexibility, portability and multi-functionalism are thus the key words of the Japanese aesthetic. From the iconic Sony Walkman of the 1980s to “ultra-compact” cameras such as Canon’s Ictus in 2000, the virtuoso miniaturization of Japanese manufacturers has had a direct impact on everyday life: walking, jogging, taking the subway, and traveling are all transformed experiences.

The other fields of creation progressively followed the industrial trend from the Second World War onwards, without ever evacuating artisanal know-how: Japanese design is a perfect mix of tradition and modernity.

Embrace the industrial design

After their defeat at the end of the Second World War, Japan was under the domination of its territory by American forces, both physically and ideologically. Thus, in addition to the presence of GIs – who had to be housed and who did not have the same cultural habits – the model of the American Way of Life was imposed: the economic, social and stylistic upheavals were considerable.

Following the American model, designer’s profession became more professional, as evidenced by the creation of institutions, such as the Japanese Design Committee in 1953, and new associations, such as the Association of Japanese Decorators in 1956. However, as usual, Japan was adapting. Thus, the state is very involved in the field, not only through the Institute of Industrial Arts (IAI, formerly IARI) but they also supported large companies, unlike the United States. Moreover, while the reign of the superstar designer is underway, Japan preferred the group culture to that of the individual: few names are put forward but collaborations between engineers, designers and marketing teams are highlighted.

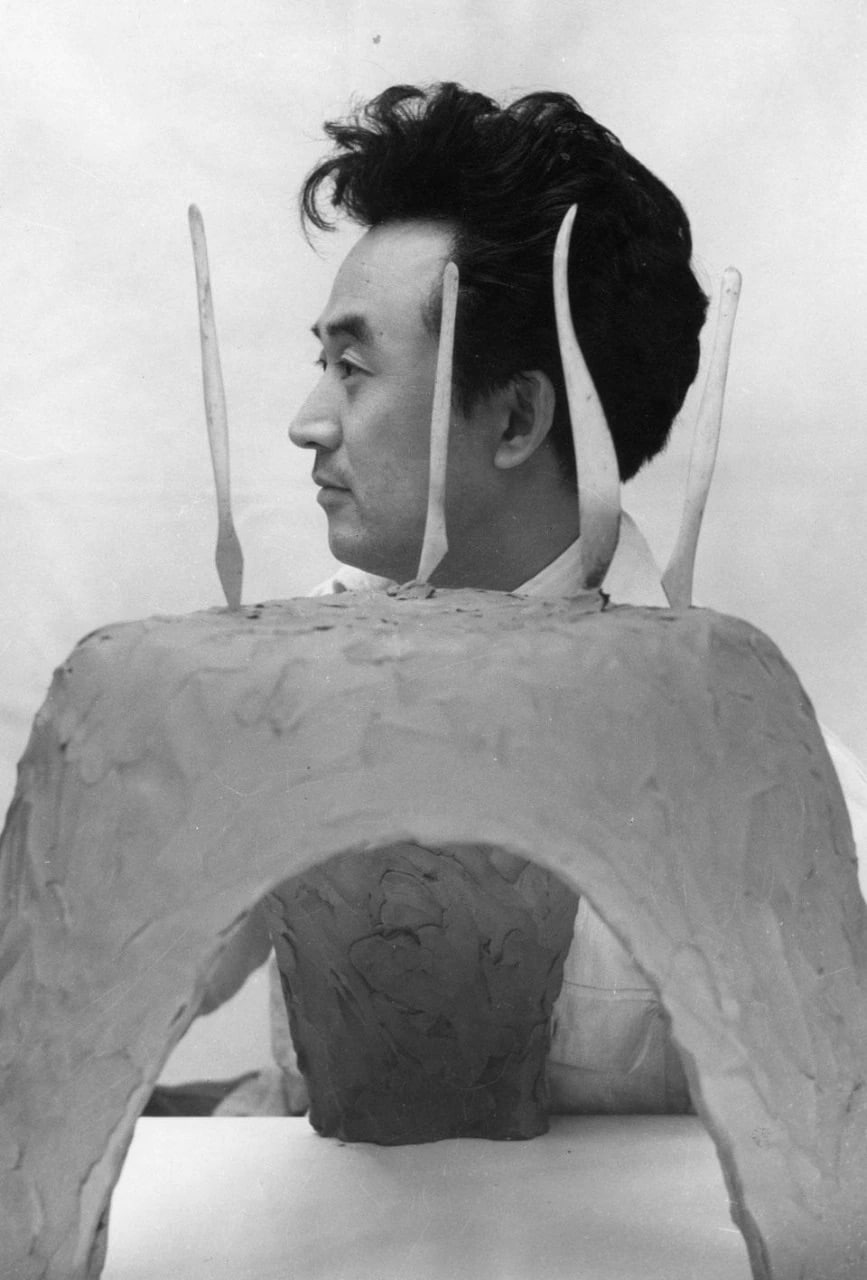

Some personalities are nevertheless placed on the front of the stage from the 1950s. The company Tendo Mokko, a sort of Japanese Knoll specialized in plywood furniture, understood this and called on renowned designers to increase its catalog: Junzo Sakakura (1901-1969), Reiko Tanabe (born in 1934), or the famous Isamu Kenmochi (1912-1971). The latter was in Bruno Taut’s entourage during his visit to Japan: he was thus in the front row to discover the novelties of modern design. His mythical collaboration with Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) resulted in the only lost copy of the Bamboo Chair: its traditional bamboo basketry combined with its organic western aesthetic perfectly sums up Japanese Post-War design, a hyphen bringing together the best of both worlds. Isamu Kenmochi, then head of the IAI, went on a professional trip to the United States in 1952 and returned determined to continue the work he had begun: to convert Japan to industrial design once and for all, while respecting their territory and their history. He founded the Association of Japanese Industrial Designers with another leading industrial designer, Sori Yanagi (1915-2011).

Internationally recognized, he was Charlotte Perriand’s assistant during her first trip. He had a privileged access to European modernism, and said that she was the one who turned him definitively towards design. His objects are among the symbols of Japanese design: from his “Butterfly” and “Elephant” stools created in 1954 to the Olympic Flame of the 1964 Olympics, and the Sony H tape recorder, becoming the first renowned designer to work with an electronics manufacturer, he is the firebrand of post-war Japanese industrial design.

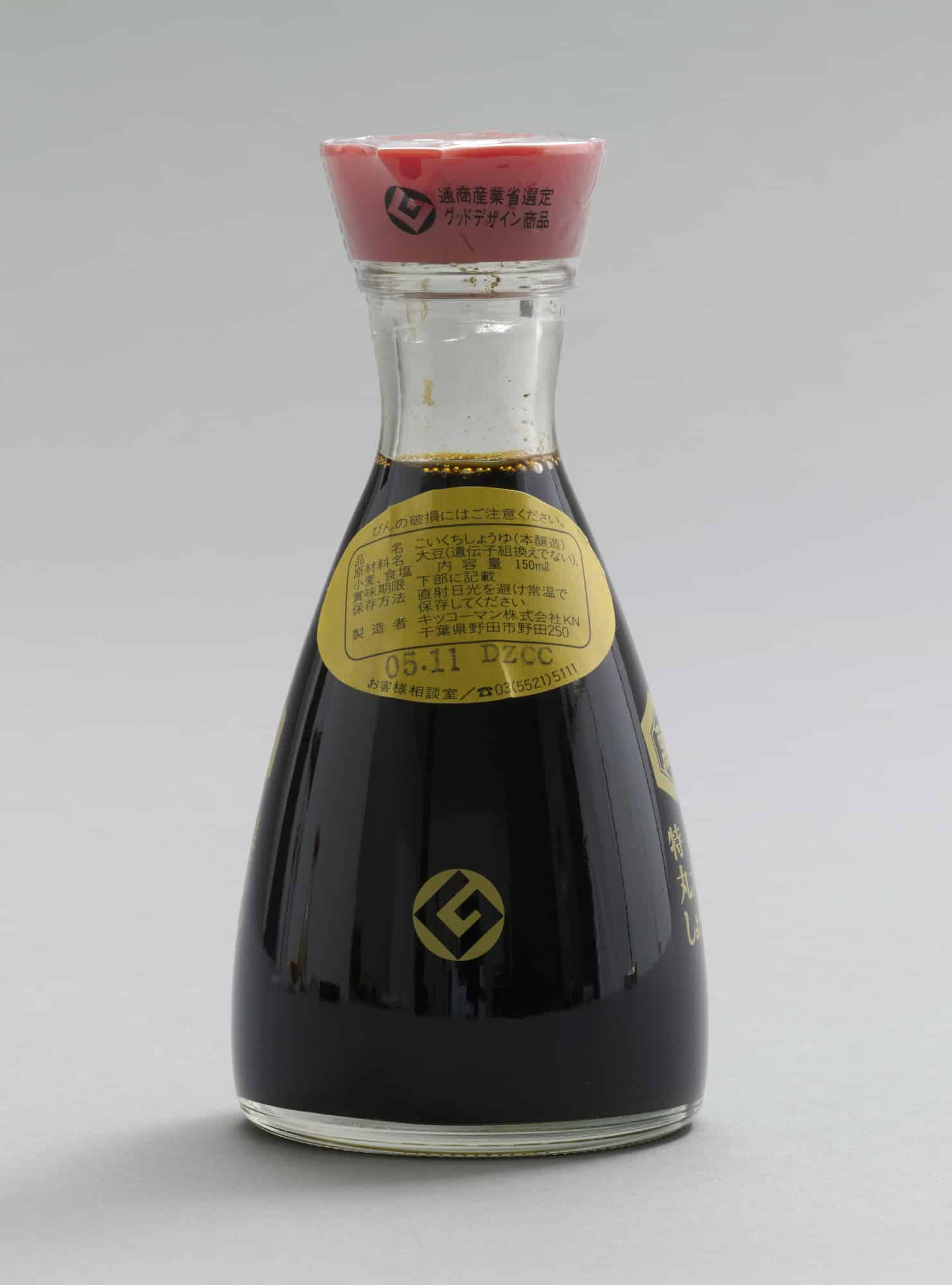

The process of recognition began in the following decades: one of the most famous objects in the world, the Kikkoman soy sauce dispenser created by Kenji Ekuan (1929-2015) in 1961. Like this icon, post-war Japanese design is characterized by simplicity, respect for materials, organic forms linked to nature and a production between tradition and modernity.

Redefine Japan: the post-modernism

Japanese design remained true to itself and it was quite unaffected by the effervescent of the ephemera trend and pop fashions of the 1960s. However, the following decades were decisive for the country: the 1970s and 1980s were to act as a catalyst, with a new generation of designers, film makers and artists redefining Japan’s image internationally.

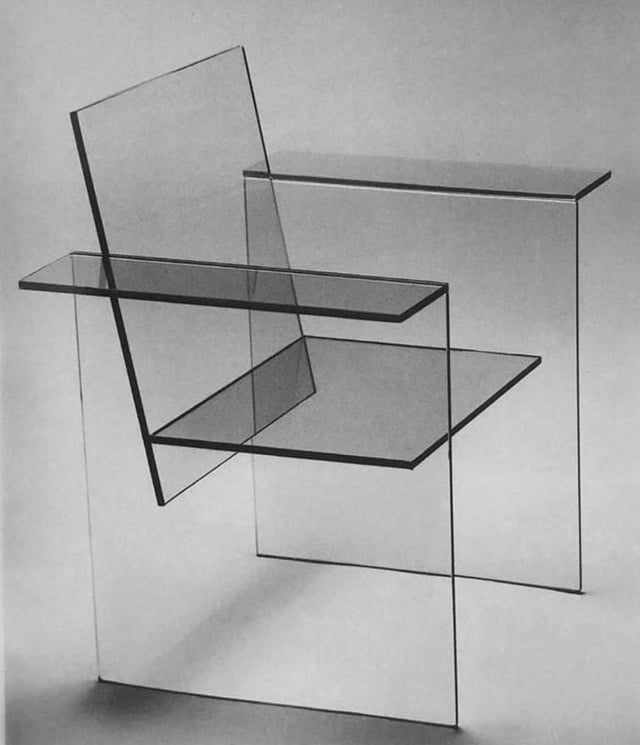

Shiro Kuramata (1934-1991) is the figurehead of this redefinition movement. He shacked up the codes: this famous designer intellectualizes the practice and creates a real narrative through his works inviting the user to question thanks to his games on gravity and transparency. The stores he created for the fashion designer Issey Miyake (1938-2022) across the globe are always an event. On the same model, Shigeru Uchida (1943-2016), another great representative of post-modernism playing as much on the form as on the content, the visible and the invisible, signs the stores of his friend fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto (born in 1943): these two duos are subversive stars in their field, which finally meet.

From now the fields of creation interpenetrate: porosity is the order of the day. Architects have always created furniture, like the great Kenzo Tange (1913-2005), and the new generation continues the practice: Tadao Ando (born 1941), Yoshi Taniguchi (born 1937) or Arata Isozaki (1931-2022) whose 1973 “Marilyn” chair is undulating with modernity, a definite achievement. The 1980s were the moment of maturity for Japanese design, embracing technology head on and enjoying success on a large scale. The “Lavinia” lamp by Masayuki Kurokawa (b. 1937) and the “Z” pen by Mitsuo Maki (b. 1948) are icons of this decade.

As mass culture unfolded and homes were flooded with seductive electronic devices, Japanese designers were exporting and selling: while the practice was not new, it was intensifying and becoming more successful. For example, Toshiyuki Kita’s (b. 1942) “Wink” chair for Cassina is a must-have, as are the works of Masanori Umeda (b. 1941) for the duchampian design group Memphis (Milano), from his alien to his ring. And designers are not the only ones to cause a sensation: certain Japanese styles and tastes are unavoidable fashions: that of minimalism, inspired by Zen, invaded the world in the 1980s and the works of the Super Potato Design studio created by Takashi Sugimoto in 1973 are good examples; that of wabi sabi also made its way and still resonates today, thanks in particular to renowned interior designers: Axel Vervoordt, fond of this spirit, distills it into the interiors of celebrities like the former Kardashian-West couple.

Japan and their aura: the globalization

The various extension of Japanese culture, both physical and aesthetic, was made possible by globalization. Several phenomena were symptoms of this: manga, although depreciated in France because they are considered as popular culture – politicians such as Ségolène Royal were against these productions – have the wind in their sails, just like Tamagochi, created in 1996, just like video games and Nintendo’s Game Boy, were the most eloquent examples of the Japanese tidal wave in our daily life. Hajime Sorayama’s (born 1947) robot dog “Aibo” for Sony is a unicum that the whole world talks about. It is through this so-called popular culture that Japan is changing: while the country is experiencing a certain economic recession at the end of the century after the economic miracle of the previous decades, gadgets will ensure a gradual recovery.

Exchanges intensified: while new designers from Europe marked the Japanese landscape, among them Jasper Morrison (born in 1959), Gae Aulenti (1927-2012), Philippe Stack (born in 1949), Ron Arad (born in 1951) or Aldo Rossi (1931-1997), the West received the Japanese wave head-on: The Muji firm, created in 1980 in Tokyo by Tsujii Takashi (1927-2013), met with considerable international success in the 1990s, spreading a true art of living.

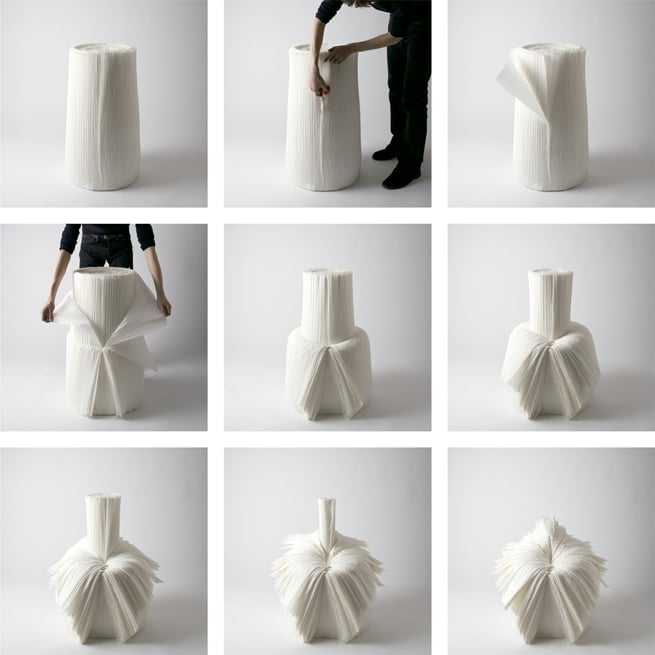

Since the 1980s, as in the rest of the world, eclecticism was de rigueur: styles are mixed and intermingled. The “Maki” armchair by Jin Kuramoto (born in 1976), playing with the codes of Japanese culture, rubbed shoulders with the “Cabbage” seat by Nendo, sensitive to ecological concerns and faithful to tradition by reusing the pleated fabrics discarded by Issey Miyake. In keeping with the times, Japanese design was plural and embraced new technologies, resulting in creations with a magnetic presence, as evidenced by the “Honey-Pop” chair created in 2000 by Takujin Yoshioka (born in 1967), whose international reputation and talent have made him work with Toyota and Kartell alike.

Despite the omnipresent globalization, there is one unwavering constant in Japanese design, which is their strength: the country never forgets their advanced craftsmanship, their history, their traditions and their know-how. One of the areas in which this is most evident is ceramics: from Nara ceramics to contemporary ones, the techniques are breathtaking. While it is common to misunderstand the dating of the form pieces as their appearance is so timeless, the contemporary creations of a Fuku Fukumoto (b. 1973) or a Futamura Yoshimi (b. 1959) are just as remarkable.

Japanese design is infinitely rich. From the Mingei to contemporary creations, it enjoys a certain aura: from post-war creations to post-modernism ones, Japanese design is always of very good quality and is characterized by clean lines, a functionalism that is unfailing and a harmonious aesthetic. While decorating trends have taken hold around the world over the century, new ones are still emerging like Japandi, proof that Japan’s influence is still immense – the 2018 “Japonisme” season in France is yet another famous example.

WA’s purpose is committed to making people (re)discover Japanese design.