A fish story

The history of Akari is multifaceted, like their creator. In an article published in Craft Horizons (Volume 14, No. 5, September-October 1954) entitled “Japanese Akari Lamps. Light, translucent, sculpture by a great sculptor”, Isamu Noguchi romanticizes the genesis of Akari and his catchphrase is a true poem: “the story of how I came to make Akari lamps starts with fish.”

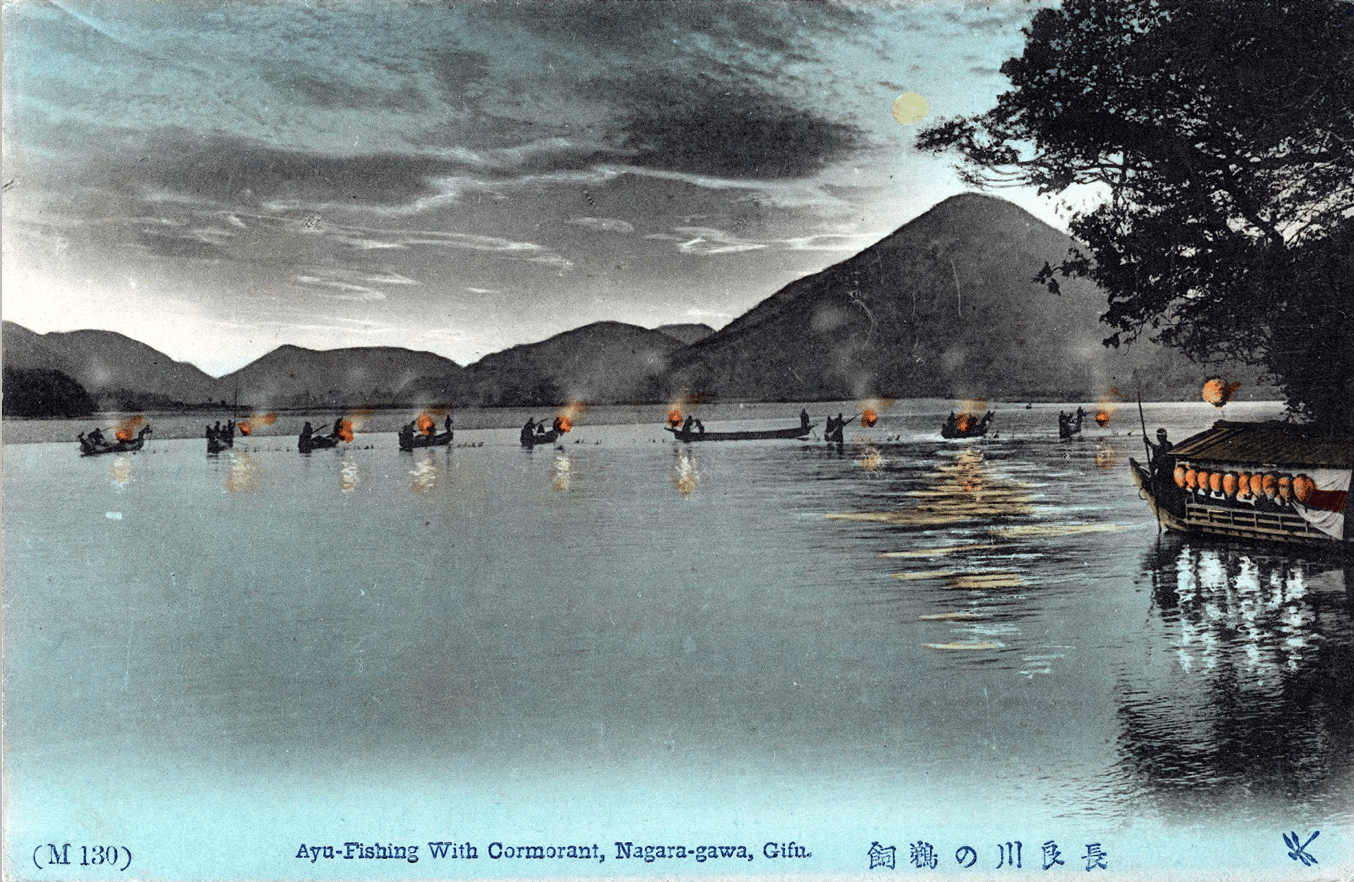

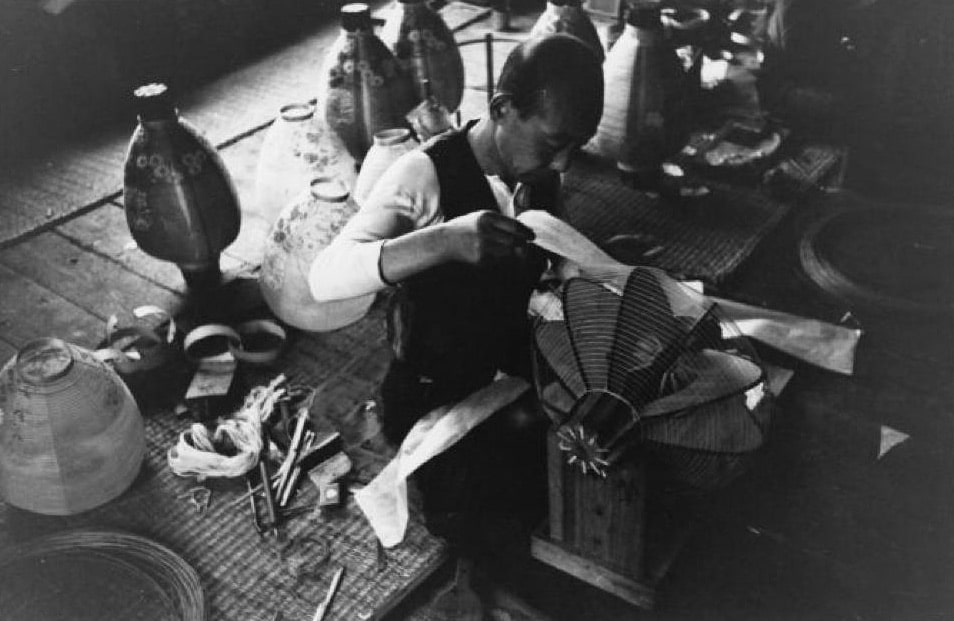

The tone is set! The rest of the development remains more pragmatic and underlines the structural aspects: “In the late spring of 1951 (on my second trip to Japan after the war), I stopped over in Gifu on my way to Kyoto, the ancient capital which is near by Gifu is famous for its cormorant fishing, and this I wished to see. […] Part and parcel of this are, of course, the Gifu lanterns which are famous all over Japan. […] Thus Gifu is still a lantern-making town, and it is inevitable that one go to see how they are made, the best place being Ozeki’s. I was much interested as a sculptor in their methods of manufacture: the frames upon which are wound the bamboo and paper; the flexibility and simplicity of which immediately suggested new possibilities of sculptural forms – a light sculpture, translucent and collapsible!”

From fishing to technique, all of Akari’s data is laid down: the fish, the lanterns, Ozeki and the sculptural dimension.

Gifu is renowned for its age-old traditions, including cormorant fishing on the Nagara river. Fishing takes place after dark: each fishing master standing in the bows of his boat uses ten to twelve birds, attached by ropes, to catch trout-like fish. Braziers attached to the prow of each boat are the only source of light. During the festival that Noguchi attended, the festivities were illuminated by chochin, hand-painted, collapsible paper and bamboo lanterns that are the region’s other main specialty. It was in this context of a discovery, celebration and fascination of local traditions that the mayor of Gifu decided to take advantage of Isamu Noguchi’s visit. Aware of his work as a designer and reputation as an artist, the mayor asked Noguchi to help revitalize the local paper lantern industry, which was in decline. This key fact that Noguchi omitted from his first account is vital in every respect: far from being a poetic story, Akari was born of a commission, as Isamu Noguchi says in numerous lectures and in an article entitled “Shapes of Light: Noguchi’s new Akari sculptures” in the January 1969 issue of Interiors magazine (No. 6). This commission came from a particular historical context.

Akari : a star is born

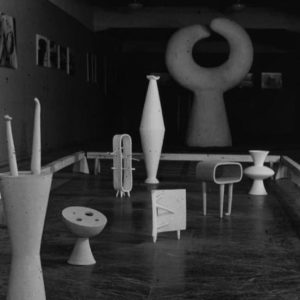

Japan is under American domination after the World War II so the American Way of Life was spread in all fields leading to deep societal changes. The advent of electricity, as well as the mainstream use of new materials, further contributed to transforming habits and customs, without ever making them disappear entirely. This is one of the specific aspects that characterizes Japan and it is a constant throughout its history: the country has always assimilated foreign influences (for example Chinese) and integrated them into its own traditions, either modifying or adapting them as necessary. Chochin lanterns belong to an age-old culture; they are made by hand in workshops where traditional expertise is handed down from one generation to the next. Technical and economic change, combined with upheaval in society, hit the chochin sector full force. With the development in trade, tourism and exports after war, the lantern’s bamboo heart was replaced by a cheap wire spiral. This major evolution allowed the lanterns to be more widely distributed, in particular to be sold as souvenirs, but resulted in an increasing industrialization of the manufacturing process that left local know-how by the wayside.When the mayor of Gifu asked Noguchi to breathe a new lease of life into the traditional paper lantern industry it wasn’t a coincidence: all the conditions were in place to ensure that the Japanese American artist would succeed in his undertaking, grasp its significance and understand its subtleties.The mayor hoped that Noguchi could use his quintessentially modern approach to revive a traditional practice and bring these two opposites together in a harmonious ensemble. Noguchi’s idea was simple, but masterful: to go back to bamboo, thereby embracing the spirit of the materials of years gone by and celebrating the splendor of an object made by hand, whilst introducing the lightbulb. No more, no less. Isamu Noguchi explains in the brochure of the exhibition “Shapes of Light” at Cordier & Ekstrom in 1968: “I thought lanterns could be luminous sculptures and set about to integrate the use of electricity and methods of support into their structure, to eliminate the traditional wooden rims (Wa), and to utilize Mino or mulberry bark paper which best diffuses the light to the surface – in sum, to enable and renew the use of lanterns.” Noguchi combined a sculptor’s understanding of form with this essential technological advance, whilst throwing himself into the adventure wholeheartedly and considerably diversifying the number of models until his death in 1988.

On accepting the mayor’s offer, he was introduced to Tameshiro Ozeki, who was at the head of Ozeki & Co, Ltd, a family business that had been making paper lanterns since 1891. On visiting the factory, Noguchi was enthralled by the multitude of shapes and the workers’ expertise. The whole city of Gifu was to be involved initially but only Ozeki finally was chosen as the manufacturer of Akari. A collaboration was born: today, Ozeki is still the only manufacturer of Akari in the world. Straight after his first visit to Ozeki, he sketched out designs for two lamps – including the 9A form – and took his drawings to the factory so that the family-run company could begin their construction. He returned to New York in the summer of 1951 with the first two Akari in his suitcase. The first four prototypes arrived in America in August 1951. From this moment on, Noguchi traveled back and forth, testing, starting over and putting the finishing touches to the shades and frames.

Akari’s life was in its childhood, and finding a name was crucial: Akari was an obvious choice. In the anthology A Sculptor’s World (New York, Harper and Row, 1968), Isamu Noguchi explains this point: “The name AKARI which I coined, means in Japanese light as illumination. It also suggests lightness as opposed to weight.” It was chosen between the spring of 1951 and fall 1952, in other words between the visit that led to their creation and the exhibition during which Noguchi presented his Akari in public for the very first time at the Museum of Modern Art Kamakura (Kamakura, Japan) from September 23rd to October 19th, 1952. This name reveals the whole essence of Akari: between shadow and light, invisibility and magnificence, illumination and sculpture, lightness and presence, Akari is beyond borders, as their creator.

Akari is therefore first of all an answer to a social and economic problem, an answer to the necessary evolution of objects over time and the need to adapt. As a new type of chōchin, Akari revived a market that was on its last legs because of changes brought about by the war. It was therefore primarily a new form of Japanese paper lantern; however, Noguchi would go on to create hundreds of variations. The history of Akari is deeply linked to the one of their creator, both his professional and personal history. Outrageously copied but without capturing their essence, the birth of Akari carries the whole DNA of the series: from the beginning all their fundamental foundations are present.

Their future evolution then has an impressive number of ways in both economic and cultural fields: from their distribution to their museum recognition, Akari’s life is a story to be told.